GREAT WOMEN

WHO HAVE

WON

SCIENTIFIC

NOBELS

THROUGHOUT HISTORY

MEDICINE

Gerty Theresa Cori

(née Radnitz)

(née Radnitz)

(1947)

Biographical

Gerty Theresa Cori,

née Radnitz, was born in Prague on August 15th, 1896. She received her primary

education at home before entering a Lyceum for girls in 1906; she

graduated in 1912 and studied for the University entrance examination, which

she took and passed at the Tetschen Realgymnasium in 1914. She entered the

Medical School of the German University of Prague and received the Doctorate in

Medicine in 1920. She then spent two years at the Carolinen Children’s Hospital

before emigrating to America with her husband, Carl, whom she married in 1920.

They worked together in Buffalo and when he moved to St. Louis, she joined him

as Research Associate. Gerty Cori was made Professor of Biochemistry in 1947.

Carl Ferdinand Cori was born in Prague on

December 5th, 1896. His father, Dr. Carl I. Cori, was Director of the Marine

Biological Station in Trieste, and it was here that young Carl spent his

childhood. He received an early introduction to science from his father and

this was stimulated on summer visits to the Tyrol, to the home of his

grandfather, Ferdinand Lippich, Professor of Theoretical Physics at Prague. He

studied at the gymnasium in Trieste and graduated in 1914 when he entered the

German University of Prague to study medicine. During World War I, he served as

a lieutenant in the Sanitary Corps of the Austrian Army on the Italian front;

he returned to University, where he studied with his future wife, Gerty, to

graduate Doctor of Medicine in 1920. He spent a year at the University of

Vienna and a year as assistant in pharmacology at the University of Graz until,

in 1922, he accepted a position as biochemist at the State Institute for the

Study of Malignant Diseases in Buffalo, New York. In 1931, he was appointed

Professor of Pharmacology at the Washington University Medical School in St.

Louis, where he later became Professor of Biochemistry.

The Cori’s have collaborated in most of their

research work, commencing in their student days and stemming from their mutual

interest in the preclinical sciences. Their first joint paper resulted from an

immunological study of the complement of human serum.

In America, they first studied the fate of sugar

in the animal body and the effects of insulin and epinephrine. The presence of

glycolysis of tumours in vivo was demonstrated. Their work on

carbohydrate metabolism passed from studies of whole animal to isolated tissues

and, later, tissue extracts and isolated enzymes, some in crystalline form,

were studied. In 1936, they isolated glucose-1-phosphate, «Cori ester», and

traced its presence to the activity of the phosphorylase, which catalyzes the

breakdown and synthesis of polysaccharides: this discovery made possible the

enzymatic synthesis of glycogen and starch in vitro. Subsequently,

phosphorylase and other enzymes were crystallized.

The Cori’s have been consistently interested in

the mechanism of action of hormones and they have carried out several studies

on the pituitary. They observed that the marked decrease in glycogen and

lowering of blood sugar in hypophysectomized rats occurred with a concomitant

increase in the rate of glucose oxidation. Subsequently, by a study of the

action of hormones on hexokinase, they observed that some pituitary extracts

inhibit this enzyme in vivo and in vitro and that insulin

counteracts this inhibition.

In addition to their own highly original personal

work, the Cori’s have always been a source of inspiration to their colleagues

at the active centres of biochemical research which they have directed. They

have contributed many articles to The Journal of Biological Chemistry

and other scientific periodicals.

Carl Cori is a member, and Gerty Cori a late

member, of the American Society of Biological Chemists, the National Academy of

Sciences, the American Chemical Society and the American Philosophical Society.

They were presented jointly with the Midwest Award (American Chemical Society)

in 1946 and the Squibb Award in Endocrinology in 1947. In addition, Gerty Cori

received the Garvan Medal (1948), the St. Louis Award (1948), the Sugar

Research Prize (1950), the Borden Award (1951) and honorary Doctor of Science

degrees from Boston University (1948), Smith College (1949), Yale (1951),

Columbia (1954), and Rochester (1955). Carl Cori, a Member of the Royal Society

( London) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, also

received the Willard Gibbs Medal (1948), the Sugar Research Foundation Award

(1947, 1950) and honorary Doctor of Science degrees from Western Reserve

University (1946), Yale (1946), Boston (1948), and Cambridge (1949). He was

President of Fourth International Congress of Biochemistry (Vienna, 1958).

Carl and Gerty Cori married in 1920 and had one

son. They became naturalized Americans in 1928. They have always been fond of

outdoor hobbies.

Dr Gerty Cori died on October 26th, 1957.

Rosalyn Yalow

(1977)

Biographical

I was born on July 19, 1921 in New York City and

have always resided and worked there except for 3 1/2 years when I was a

graduate student at the University of Illinois.

I was born on July 19, 1921 in New York City and

have always resided and worked there except for 3 1/2 years when I was a

graduate student at the University of Illinois.

Perhaps the earliest memories I have are of being

a stubborn, determined child. Through the years my mother has told me that it

was fortunate that I chose to do acceptable things, for if I had chosen

otherwise no one could have deflected me from my path.

My mother, née Clara Zipper, came to America from

Germany at the age of four. My father, Simon Sussman, was born on the Lower

East Side of New York, the Melting Pot for Eastern European immigrants. Neither

had the advantage of a high school education but there was never a doubt that

their two children would make it through college. I was an early reader,

reading even before kindergarten, and since we did not have books in my home,

my older brother, Alexander, was responsible for our trip every week to the

Public Library to exchange books already read for new ones to be read.

By seventh grade I was committed to mathematics.

A great chemistry teacher at Walton High School, Mr. Mondzak, excited my

interest in chemistry, but when I went to Hunter, the college for women in New

York City’s college system (now the City University of New York), my interest

was diverted to physics especially by Professors Herbert N. Otis and Duane

Roller. In the late ’30’s when I was in college, physics, and in particular

nuclear physics, was the most exciting field in the world. It seemed as if

every major experiment brought a Nobel Prize. Eve Curie had just published the

biography of her mother, Madame Marie

Curie, which should be a must on the reading list of every young aspiring

female scientist. As a Junior at college, I was hanging from the rafters in

Room 301 of Pupin Laboratories (a physics lecture room at Columbia University)

when Enrico

Fermi gave a colloquium in January 1939 on the newly discovered nuclear

fission – which has resulted not only in the terror and threat of nuclear

warfare but also in the ready availability of radioisotopes for medical

investigation and in hosts of other peaceful applications.

I was excited about achieving a career in

physics. My family, being more practical, thought the most desirable position

for me would be as an elementary school teacher. Furthermore, it seemed most

unlikely that good graduate schools would accept and offer financial support

for a woman in physics. However my physics professors encouraged me and I

persisted. As I entered the last half of my senior year at Hunter in September

1940 I was offered what seemed like a good opportunity. Since I could type,

another of my physics professors, Dr. Jerrold Zacharias, now at Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, obtained a part time position for me as a secretary to

Dr. Rudolf Schoenheimer, a leading biochemist at Columbia University’s College of

Physicians and Surgeons (P&S). This position was supposed to provide an

entrée for me into graduate courses, via the backdoor, but I had to agree to

take stenography. On my graduation from Hunter in January 1941, I went to

business school. Fortunately I did not stay there too long. In mid-February I

received an offer of a teaching assistantship in physics at the University of

Illinois, the most prestigious of the schools to which I had applied. It was an

achievement beyond belief. I tore up my stenography books, stayed on as

secretary until June and during the summer took two tuition-free physics

courses under government auspices at New York University.

In September I went to Champaign-Urbana, the home

of the University of Illinois. At the first meeting of the Faculty of the

College of Engineering I discovered I was the only woman among its 400 members.

The Dean of the Faculty congratulated me on my achievement and told me I was

the first woman there since 1917. It is evident that the draft of young men into

the armed forces, even prior to American entry into the World War, had made

possible my entrance into graduate school.

On the first day of graduate school I met Aaron

Yalow, who was also beginning graduate study in physics at Illinois and who in

1943 was to become my husband. The first year was not easy. From junior high

school through Hunter College, I had never had boys in my classes, except for a

thermodynamics course which I took at City College at night and the two summer

courses at NYU. Hunter had offered a physics major for the first time in

September 1940 when I was an upper senior. As a result my course work in

physics had been minimal for a major – less than that of the other first year

graduate students. Therefore at Illinois I sat in on two undergraduate courses

without credit, took three graduate courses and was a half-time assistant

teaching the freshman course in physics. Like nearly all first-year teaching

assistants, I had never taught before – but unlike the others I also undertook

to observe in the classroom of a young instructor with an excellent reputation

so that I could learn how it should be done.

It was a busy time. I was delighted to receive a

straight A in two of the courses, an A in the lecture half of the course in

Optics and an A- in its laboratory. The Chairman of the Physics Department,

looking at this record, could only say “That A- confirms that women do not do

well at laboratory work”. But I was no longer a stubborn, determined child, but

rather a stubborn, determined graduate student. The hard work and subtle

discrimination were of no moment.

Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 brought our

country into the war. The Physics Department was becoming decimated by loss of

junior and senior faculty to secret scientific work elsewhere. The campus was

filled with young Army and Navy students sent to the campus by their respective

Services for training. There was a heavy teaching load, graduate courses, an

experimental thesis requiring long hours in the laboratory, marriage in 1943, war-time

housekeeping with its shortages and rationing, and in January 1945 a Ph.D. in

Nuclear Physics. My thesis director was Dr. Maurice Goldhaber, later to become

Director of Brookhaven National Laboratories. Support and encouragement came

from the Goldhabers. Dr. Gertrude Goldhaber, his wife, was a distinguished

physicist in her own right, but with no University position because of nepotism

rules. Since my research was in nuclear physics I became skilled in making and

using apparatus for the measurement of radioactive substances. The war was

continuing. I returned to New York without my husband in January 1945 since

completion of his thesis was delayed and I accepted a position as assistant

engineer at Federal Telecommunications Laboratory, a research laboratory for

ITT – the only woman engineer. When the research group in which I was working

left New York in 1946, I returned to Hunter College to teach physics, not to

women but to returning veterans in a preengineering program.

My husband had come to New York in September

1945. We established our home in an apartment in Manhattan, then in a small

house in the Bronx. It and a full-time teaching position at Hunter were hardly

enough to occupy my time fully. By this time my husband was in Medical Physics

at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. Through him I met Dr. Edith Quimby, a

leading medical physicist at P&S. I volunteered to work in her laboratory

to gain research experience in the medical applications of radioisotopes. She

took me to see “The Chief”, Dr. G. Failla, Dean of American medical physicists.

After talking to me for a while, he picked up the phone, dialed, and I heard

him say “Bernie, if you want to set up a radioisotope service, I have someone

here you must hire.” Dr. Bernard Roswit, Chief of the Radiotherapy Service at

the Bronx Veterans Administration Hospital and I appeared to have no choice;

Dr. Failla had spoken.

I joined the Bronx VA as a part time consultant

in December 1947, keeping my position at Hunter until the Spring Semester of

1950. During those years while I was teaching full-time, I equipped and

developed the Radioisotope Service and started research projects together with

Dr. Roswit and other physicians in the hospital in a number of clinical fields.

Though we started with nothing more than a janitor’s closet and a small grant

to Dr. Roswit from a veterans’ group, eight publications in different areas of

clinical investigation resulted from this early work. The VA wisely made a

commitment to set up Radioisotope Services in several of its hospitals around

the country because of its appreciation that this was a new field in which

research had to proceed pari passu with clinical application. Our hospital

Radioisotope Service was one of the first supported under this plan.

In January 1950 I chose to leave teaching and

join the VA full time. That Spring when he was completing his residency in

internal medicine at the Bronx VA, Dr. Solomon A. Berson and I met and in July

he joined our Service. Thus was to begin a 22 year partnership that lasted

until the day of his death, April 11, 1972. Unfortunately, he did not survive

to share the Nobel Prize with me as he would have had he lived.

During that period Aaron and I had two children,

Benjamin and Elanna. We bought a house in Riverdale, less than a mile from the

VA. With sleep-in help until our son was 9, and part-time help of decreasing

time thereafter, we managed to keep the house going and took pride in our

growing children: Benjamin, now 25, is a systems programmer at the CUNY

Computer Center; Elanna, now 23, is a third year doctoral candidate in

Educational Psychology at Stanford University. She has just married Daniel Webb

and is with us on part of her honeymoon.

But to return to the scientific aspects of my

life, after Sol joined our Service, I soon gave up collaborative work with

others and concentrated on our joint researches. Our first investigations

together were in the application of radioisotopes in blood volume

determination, clinical diagnosis of thyroid diseases and the kinetics of iodine

metabolism. We extended these techniques to studies of the distribution of

globin, which had been suggested for use as a plasma expander, and of serum

proteins. It seemed obvious to apply these methods to smaller peptides, i.e.,

the hormones. Insulin was the hormone most readily available in a highly

purified form. We soon deduced from the retarded rate of disappearance of

insulin from the circulation of insulin-treated subjects that all these

patients develop antibodies to the animal insulins. In studying the reaction of

insulin with antibodies, we appreciated that we had developed a tool with the

potential for measuring circulating insulin. It took several more years of work

to transform the concept into the reality of its practical application to the measurement

of plasma insulin in man. Thus the era of radioimmunoassay (RIA) can be said to

have begun in 1959. RIA is now used to measure hundreds of substances of

biologic interest in thousands of laboratories in our country and abroad, even

in scientifically less advanced lands.

It is of interest from this brief history that

neither Sol nor I had the advantage of specialized post-doctoral training in

investigation. We learned from and disciplined each other and were probably

each other’s severest critic. I had the good fortune to learn medicine not in a

formal medical school but directly from a master of physiology, anatomy and

clinical medicine. This training was essential if I were to use my scientific

background in areas in which I had no formal education.

Sol’s leaving the laboratory in 1968 to assume

the Chairmanship of the Department of Medicine at the Mount Sinai School of

Medicine and his premature death 4 years later were a great loss to

investigative medicine. At my request the laboratory which we shared has been

designated the Solomon A. Berson Research Laboratory so that his name will

continue to be on my papers as long as I publish and so that his contributions

to our Service will be memoralized. At present my major collaborator is a young,

talented physician, Dr. Eugene Straus, who joined me in 1972, first as a

Fellow, then as Research Associate and now as Clinical Investigator.

Through the years Sol and I together, and now I

alone, have enjoyed the time spent with the “professional children”, the young

investigators who trained in our laboratory and who are now scattered

throughout the world, many of whom are now leaders in clinical and

investigative medicine. In the training in my laboratory the emphasis has been

not only in learning our research techniques but also our philosophy. I have

never aspired to have, nor do I now want, a laboratory or a cadre of

investigators-in-training which is more extensive than I can personally

interact with and supervise.

The laboratory since its inception has been

supported solely by the Veterans Administration Medical Research Program and I

acknowledge with gratitude its confidence in me and its encouragement through

the years. My hospital is now affiliated with The Mount Sinai School of

Medicine where I hold the title of Distinguished Service Professor. I am a

member of the National Academy of Sciences. Honors which I have received

include, among others: Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award; A. Cressy

Morrison Award in Natural Sciences of the N.Y. Academy of Sciences; Scientific

Achievement Award of the American Medical Association; Koch Award of the

Endocrine Society; Gairdner Foundation International Award; American College of

Physicians Award for distinguished contributions in science as related to

medicine; Eli Lilly Award of the American Diabetes Association; First William

S. Middleton Medical Research Award of the VA and five honorary doctorates.

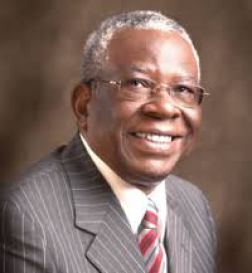

MR. TOYOTA -Elizade Motors

CHIEF MICHAEL ADE

OJO

How This African Entrepreneur Built A

Multi-Million Dollar Business With Almost No Money

It’s

a great thing to dream, as long as when you’re awake, your daily activities

are tied around achieving your goals. Millionaires are made everyday, but

what’s more intriguing, are the few who grow a multi-million Dollar

conglomerate from practically nothing.

Such

is the success story of Nigerian Dollar multi-millionaire Chief Michael

Ade-Ojo, the founder and CEO of the Elizade Group of companies.

Starting Out

Michael

was born in Nigeria on June 14, 1938 to two modest parents. At a very young

age, he became a street vendor, and started selling charcoal, food, &

firewood to help make ends meet.

Although

born in a time when there was little to no financial aid for the less

privileged, and parents believed a lot lesser in education, he still

successfully made it through high school, and later got a degree in Business

Administration from the university of Nigeria Nsukka

After

his graduation, he joined the work force at CFAO motors; a French distribution

company. This same company had paid the tuition for his last two years in the

university.

In

1966, while still working as a salesman for CFAO motors, he successfully sold

20 trucks to the Electricity Corporation of Nigeria, but to his dismay, his

manager took credit for the sale, which led to a protest by Michael, followed

with him losing his job by the end of the year.

After

his ousting at CFAO motors, he moved on, and got a job at British Petroleum

(BP). Within three months of his employment, he increased the sales of his

local division by 25%. But just as he was unfortunate with his previous

employment, his new boss took credit for the outstanding growth, and this left

him aggrieved and lost in thoughts.

The Big Break!

While

in Lagos, Nigeria, during his annual British Petroleum (BP) holiday, he

decided to take a daring step to approach the RT Brisco Group; an importer and

distributor of trucking and automobile equipments. He made them an offer to

sell their equipments for a commission on every successful sale.

After

careful consideration, the RT Brisco Group decided to give him a trial. In just

four months after he sealed the deal with Brisco, he sold about 40 cars. The

commissions earned from the total sales, were overwhelmingly higher than his

yearly salary at BP. This motivated him to quit his job, and pursue his dreams.

In

1971, he started the company, Elizade Independent Agencies (EIA), with his

wife, Elizabeth Wuraola Ojo. The name Elizade, was derived from both his wife’s

name, Elizabeth, and his name, Ade. His company focused on the distribution of

automobiles in Nigeria, especially Japanese cars.

He

acquired the license to import Toyota Cars, with the name, Toyota Nigeria

Limited, and single handedly, made the car brand, the most sought-after

automobile brand in Nigeria. He later went on to acquire 100% of RT Briscoe in

Nigeria, and subsequently acquired more shares, to make his total holdings in

Toyota Nigeria Limited, sum up to 74%.

Today,

his conglomerate consists of Toyota Nigeria Limited, RT Briscoe Nigeria,

Elizade Auto Land, Classic Motors Limited, Crow Motors Nigeria Limited, Elizade

University, Okin Travels Limited, and a host of other investments. He’s also on

the board of directors of several Nigeria banks and other companies such as

Ecobank, First City Monument Bank, and SMT Nigeria Limited (the official

distributors of Mack trucks, Volvo trucks, & Volvo Construction

Equipments).

The

story of Micheal Ade-Ojo is one of impeccable success. It shows an individual

who not only mastered his craft, but also knows when and how to take advantage

of opportunities before others start to notice.

He

started small, but most importantly, he started right!